Do Early Startups Really Need a TPM Or Do They Need the Outcomes a TPM Provides?

Early-stage startups often ask the same question.

Do we need a TPM(Technical Program Manager)?

The honest answer is usually yes.

But the practical answer is often not yet.

This post is not about whether TPMs are valuable.

It is about how the function of a TPM can be handled before a team is ready to hire one.

Why TPMs Exist in the First Place

A Technical Program Manager exists to solve a real problem.

As systems grow more complex, teams do too.

Someone needs to track dependencies, surface risks, explain delays, and translate engineering reality into something the business can act on.

In large organizations, that role is essential.

In early startups, however, the same role often becomes a bottleneck.

The Early-Stage Reality

Hiring an experienced TPM early is expensive.

So the responsibility usually falls on a CTO or tech lead.

At first, it works.

Over time, coordination expands.

Decision-making slows down.

Ownership becomes less clear.

Development turns into negotiation.

This is not a people problem.

It is a structure problem.

Reframing the Question

The real question is not:

“Should we hire a TPM?”

It is:

“How does the work of a TPM get done?”

If you break the role down, it usually consists of two core functions:

- Visibility and explanation

- Decision support and coordination

Those functions do not have to live entirely inside one person.

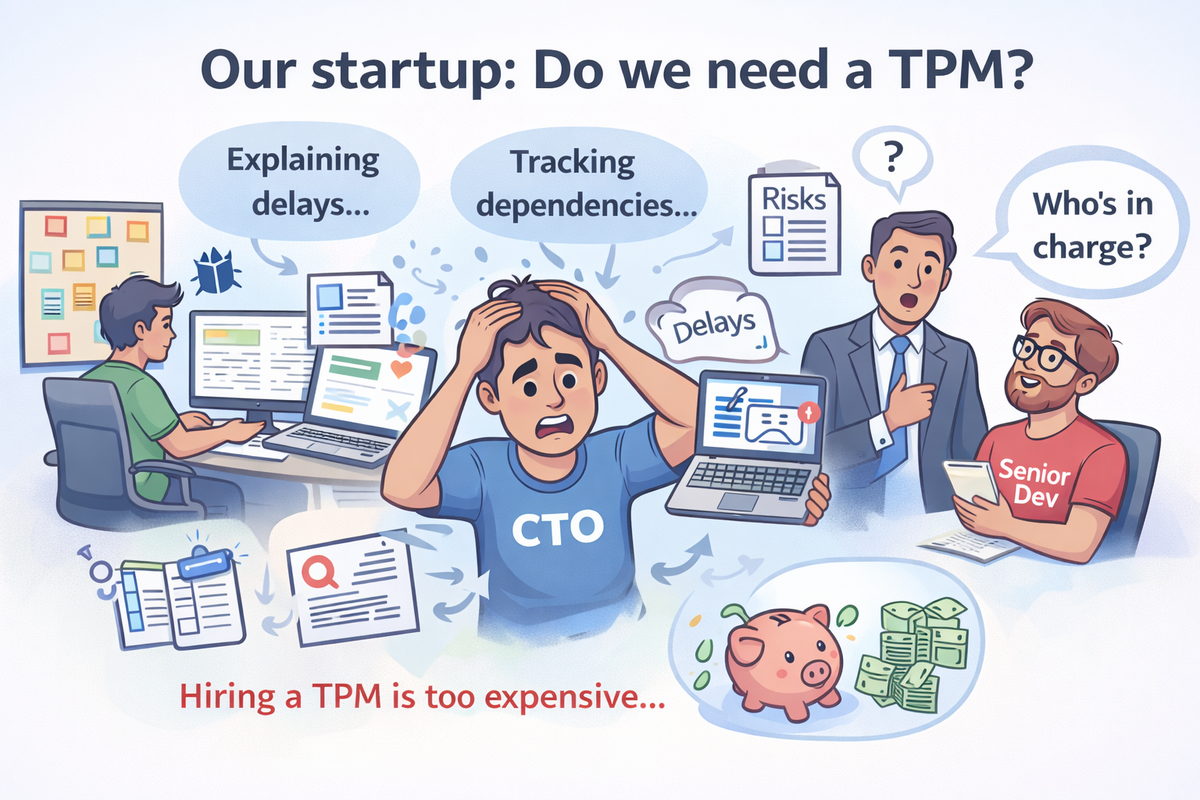

The System Approach: From Activity to Ownership

Below is the structure we use to replace guesswork with clarity.

Step 1. Engineering Activity

Everything starts with real work.

Commits

Pull requests

Issues

Reviews

This is the ground truth of what is actually happening, not what was planned or reported.

Step 2. BCTO

Visibility and Explanation

BCTO turns raw engineering activity into explainable signals.

- What is progressing and what is not

- Where time is actually going

- Why delays occur without blaming individuals

This replaces status meetings with observable data.

The goal is not evaluation.

The goal is shared understanding.

Step 3. Aline.team

Decision Support and Recommendations

Aline.team builds on top of that visibility.

By learning from developer patterns and team dynamics, it helps answer harder questions:

- Who is best suited for this task

- Where intervention will have the biggest impact

- Why a particular allocation makes sense

It does not make decisions for teams.

It makes decisions defensible.

Step 4. Technical Leadership

Clear Decisions and Ownership

The final decision still belongs to people.

Leaders decide.

Teams execute.

Outcomes are owned.

The difference is that decisions are no longer driven by seniority, volume, or intuition alone.

They are supported by structure.

This Is Not About Replacing TPMs

BCTO and Aline.team are not designed to eliminate TPMs.

They are designed to:

- Let teams operate clearly before hiring one

- Allow TPMs to focus on judgment instead of data collection

- Prevent early teams from collapsing into coordination overhead

In practice, this covers 70 to 80 percent of what TPMs do manually.

The Takeaway

Strong teams are not built on perfect consensus.

They are built on:

- Clear ownership

- Explainable decisions

- Structures that scale before people do

If a TPM is a role,

then BCTO and Aline.team are how that role becomes a system.

If you are building an early engineering team and feel like coordination is slowing you down,

the problem may not be people.

It may be the absence of a visible decision structure.